The winner's curse

Part 8 of 9: Statistical fallacies that cost millions

Previous: Stretching the truth with a short axis | Next: Delusional sophistication and narrative nonsense

You're the head of product strategy at a growing SaaS company, and you're studying your most successful competitors to understand what makes them tick. You analyze Facebook's early growth hacking tactics, Google's minimalist design philosophy, and Airbnb's viral referral system.

Based on your research, you convince your team to adopt similar strategies: aggressive growth hacking, stripped-down interfaces, and incentivized referrals. After all, if it worked for the giants, it should work for you, right?

Eighteen months later, your growth has stagnated, user experience has suffered, and your referral program is hemorrhaging money. What went wrong?

Two words: survivorship bias.

For every Facebook that succeeded with growth hacking, there were hundreds of companies that tried identical tactics and failed spectacularly. For every Google that thrived with minimalism, countless startups discovered that simple design wasn't enough. For every Airbnb that built viral loops, thousands of companies burned through funding chasing referral strategies that never worked.

You studied only the winners, completely ignoring the massive graveyard of companies that tried the same approaches and failed.

Reading the holes, not the hits

The most famous example of survivorship bias comes from World War II, and it illustrates the concept so perfectly that it's become legendary among statisticians.

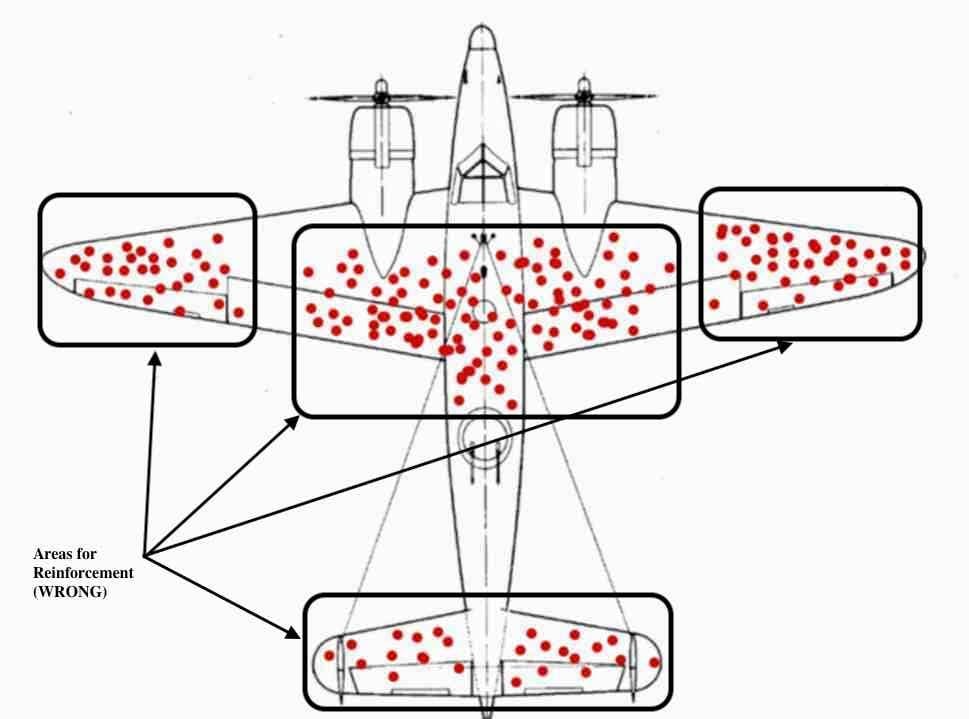

Allied bombers returning from missions over Nazi-occupied Europe arrived back at base riddled with bullet holes. Military engineers studied the damage patterns carefully, noting that hits were heavily concentrated on the wings and fuselage. The natural conclusion seemed obvious: reinforce the areas that were taking the most damage.

But Abraham Wald, a statistician with the Statistical Research Group, saw something everyone else missed.

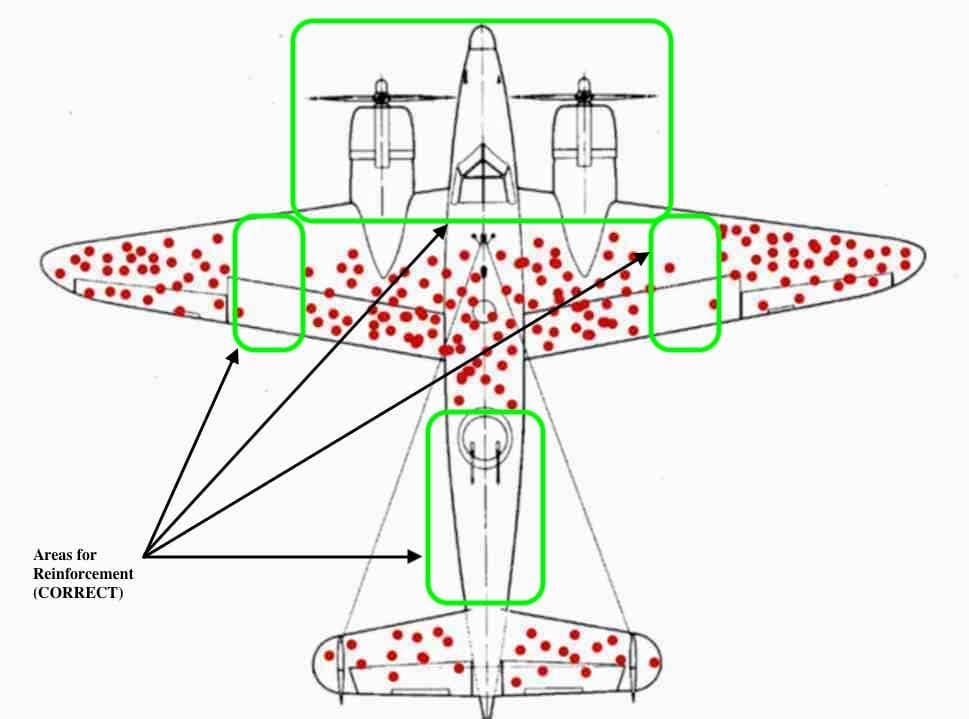

The planes they were examining had survived their missions despite taking damage to wings and fuselage. The bombers that took hits to engines, cockpit, and other critical systems never made it back to base for analysis — they were shot down over enemy territory.

The areas without bullet holes were actually the most vulnerable, because planes hit in those locations didn't survive to tell their story.

Wald's insight was revolutionary: the data you can see is fundamentally biased by the fact that it survived to be observed. The most important information often comes from what's missing, not what's present.

Thanks to Wald's analysis, the military reinforced the "undamaged" areas instead, likely saving countless lives.

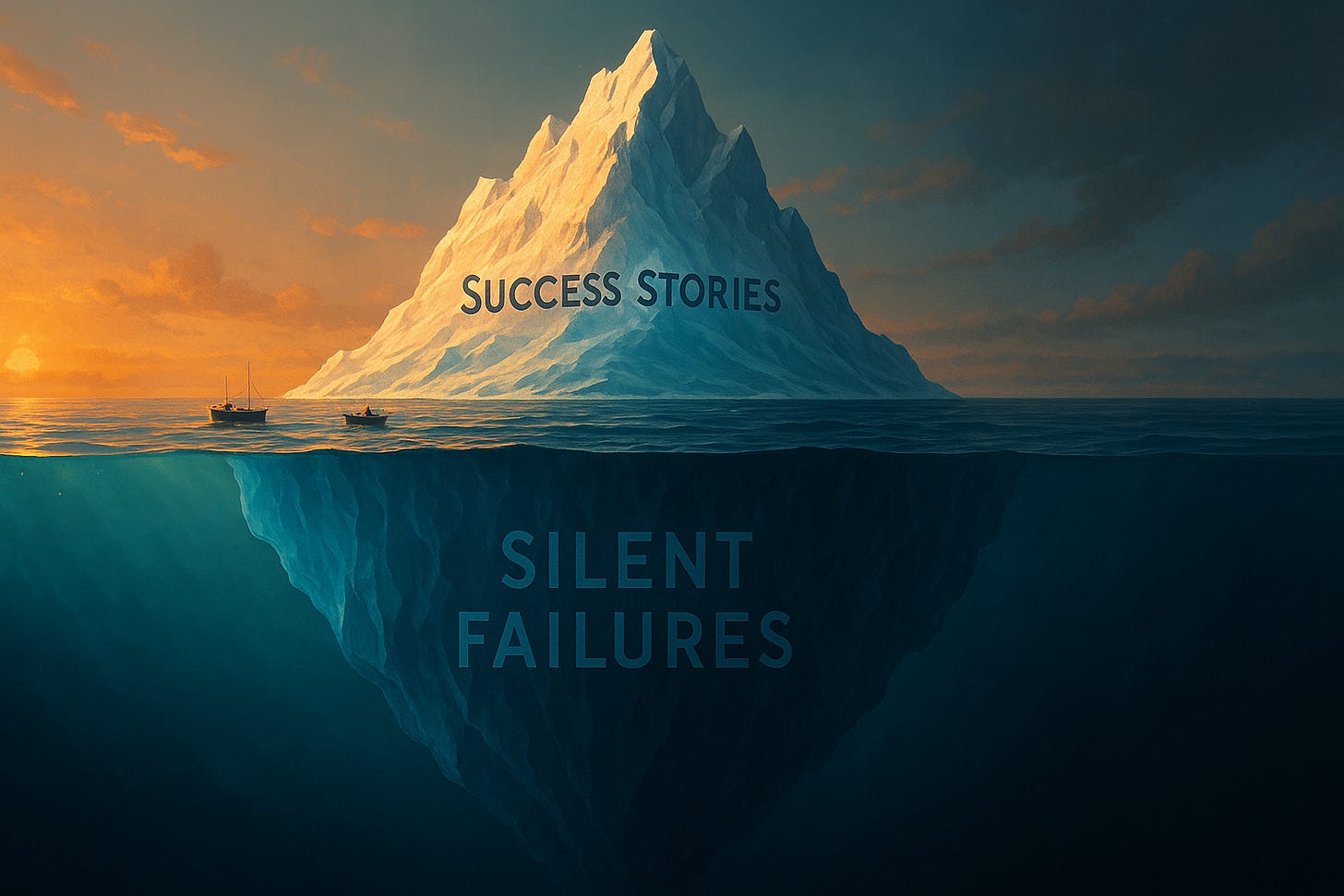

For every Facebook, a thousand invisible failures

Nassim Taleb, author of Antifragile and several other influential books, calls this "the silent grave" phenomenon. For every visible winner, there's an invisible population of identical attempts that failed.

Consider the technology industry's obsession with analyzing successful startups:

Facebook's dorm room origin story gets told endlessly, but we ignore the thousands of companies started by college students that never gained traction

Apple's design perfectionism is legendary, but we don't study the hundreds of companies that obsessed over design and still failed

Amazon's long-term thinking is celebrated, but we overlook the e-commerce companies that also prioritized long-term growth and went bankrupt

The graveyard of failed companies is vastly larger than the small group of survivors, but we only have access to study the survivors.

Stone Age brains, digital age problems

Like many of the other statistical fallacies and cognitive biases we've covered, survivorship bias isn't a character flaw — it's a predictable quirk of human psychology that served us well for thousands of years.

We're biologically wired to:

Pay attention to successful group members (useful for learning survival strategies)

Remember dramatic, positive outcomes more vividly than mundane failures

Seek patterns in success stories that we can replicate

Ignore boring, unsuccessful attempts that don't offer clear lessons

In small tribal environments, copying successful behavior was generally smart. The hunter who brought back the most food, the leader who won battles, the farmer who grew the best crops — their methods were worth emulating.

But in our complex modern world, this instinct can lead us astray. Success often depends on timing, luck, market conditions, and countless other factors that winners either don't recognize or don't mention.

This doesn't mean we should dismiss all success stories.

Sometimes successful people do offer genuinely valuable insights. The key is being methodical about how we analyze success patterns.

Don't just study the winners; study the losers too. If you find a technique that winners consistently employ and losers consistently avoid — and the causal mechanism makes rational sense — that's probably worth considering.

For instance, if successful startups obsessively gather customer feedback while failed startups neglect this practice, and you can explain why this would increase success odds (iterating based on user needs leads to better product-market fit), then this becomes meaningful data rather than mere correlation.

The goal isn't to become paralyzed by the possibility that any advice might be wrong. It's to approach success stories with appropriate skepticism, always remembering that for every visible winner, there's an invisible population who tried identical strategies and failed.

The business advice industrial complex

Nowhere is survivorship bias more prevalent than in the business advice industry.

What we see:

Successful entrepreneurs sharing their "proven" strategies

Bestselling books about the habits of highly effective people

Case studies of companies that "did everything right"

Conference speakers telling inspiring success stories

What we miss:

Entrepreneurs who used identical strategies and failed

Highly effective people whose habits didn't prevent failure

Companies that followed the same playbook and went bankrupt

The statistical reality that most new ventures fail regardless of strategy

The advice industry has a built-in survivorship bias problem: failed entrepreneurs don't get book deals, bankrupt companies don't sponsor conferences, and unsuccessful leaders don't become keynote speakers.

Watch for the silent grave

Red flags to watch for:

Success-only analysis — When someone studies only winners, ask: "What about those who tried the same thing and failed?"

Extraordinary claims — If a strategy supposedly has a "95% success rate," demand to know the total sample size and base rates

Survivor celebrity — Be skeptical of advice from people whose main qualification is surviving something difficult

What to do instead:

Study failures actively — For every success story you encounter, seek out negative examples of the same approach

Test small first — Don't bet everything on "proven" strategies; run small experiments to see what actually works in your context

Ask about base rates — Before adopting any strategy, understand how often it actually succeeds across all attempts, not just visible winners

When copying winners backfires

A few more examples to consider:

The unicorn strategy trap

A venture capital firm analyzed all the unicorn startups (companies valued over $1 billion) from the past decade. They identified common patterns: aggressive growth spending, platform business models, and venture-backed expansion strategies.

Based on this analysis, they shifted their entire investment thesis toward companies following the "unicorn playbook." Results were disastrous — most of their portfolio companies burned through funding without achieving sustainable growth.

What they missed: For every unicorn that succeeded with aggressive growth, there were hundreds of companies that tried identical strategies and failed. The successful approach was rare precisely because it was difficult to execute.

The social media marketing mirage

A marketing agency studied viral social media campaigns from major brands, identifying common elements: humor, controversy, user-generated content, and influencer partnerships.

They built their entire service offering around replicating these "proven" viral strategies. Most campaigns flopped, and client relationships soured when promised viral success didn't materialize.

The reality: For every viral campaign they studied, thousands of similar campaigns failed to gain traction. Virality depends on factors (timing, cultural context, luck) that can't be reliably replicated.

The leadership style mismatch

An executive read extensive case studies about transformational leaders who succeeded through bold, disruptive decision-making. He adopted an aggressive leadership style, making dramatic organizational changes and challenging conventional wisdom.

His tenure was a disaster. Employee morale plummeted, key talent left, and performance declined. He was fired within two years.

What he didn't consider: Bold leadership works for some people in some situations, but confirmation bias led him to study only the success stories. Countless leaders have failed by being too aggressive or disruptive.

The Wald Principle

Survivorship bias distorts our understanding of success by making us focus only on the winners while ignoring the vastly larger population of identical attempts that failed.

Every visible success story represents not just one winner, but potentially hundreds or thousands of invisible failures.

Before adopting any strategy based on success stories:

Ask about the failures — what happened to people who tried the same approach?

Understand the base rates — what percentage of attempts actually succeed?

Seek negative examples — actively look for cautionary tales

Test incrementally — don't bet everything on "proven" approaches

Remember the silent grave — the most important data might be missing

The goal isn't to become paralyzed by failure rates or to ignore success stories entirely. It's to develop a more complete, realistic understanding of what actually works and how often.

Remember Abraham Wald's insight: sometimes the most important information comes from what's missing, not what's visible.

This is Part 8 of our 9-part series on statistical fallacies. Subscribe below to get the final post delivered to your inbox.

Next time: In our final post, we'll explore the fallacy that ties together many of the others we've discussed: the narrative fallacy. I'll show you why our brain's love of coherent stories makes us dangerously overconfident in our ability to predict complex systems, and how this cognitive bias amplifies every other statistical trap we've covered.

Catch up on the entire series: